The Landscape of European EV charging

15 October, 2019

Alongside the affordability of electric vehicles, the availability of charging infrastructure is widely acknowledged as a key enabler for the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs).

While this point is well known, much discussion is had between stakeholders and policy makers over what comes first: charging infrastructure or EV adoption. Should we deploy chargers as more and more EVs hit the roads, or should we build out chargers first, and encourage EV adoption? It’s a classic “chicken or egg” scenario, to quote the European Federation for Transport & Environment.

Although the causality between the two hasn’t been widely investigated, researchers in Sweden at IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute and the University of Gothenburg have attended to the matter and delivered findings that shed light on the dynamics at play.

“Our studies show that municipal investment in charging points has led to an increased number of electric cars, especially in large cities. These are the first studies that investigate the causality between a number of local instruments and newly registered electric vehicles in Swedish boroughs,” said IVL research fellow, Magnus Hennlock about the results of analysis of data from 2010 to 2016.

This positive effect of municipal charging points in encouraging uptake of EVs was found to be more pronounced in larger urban centers than in rural areas.

The researchers also concluded that in urban environments charging points are best placed in highly populated areas, since the main urban barrier to EV adoption is limited charging possibilities at home. In contrast, smaller municipalities should place chargers close to roads which carry the largest volumes of traffic – an action that would serve to both increase visibility of chargers and reduce range anxiety for commuters.

While the studies were conducted on Swedish data, Magnus told Northvolt: “Most likely the situation is similar in the other Nordic countries. When it comes to the rest of Europe, I can imagine that the larger sizes of European cities come into play. Urbanization and larger cities bring a larger share of multi-family dwellings, making the role of municipalities even more critical than what we see in the Nordic countries.”

The findings should be noted by both private and public actors involved in establishing charging infrastructure. Clearly both have parts to play, but public municipalities carry particular responsibilities considering their role in city and suburban planning, and securing developments which deliver on climate and emissions targets.

On this point, Magnus said: “Local authorities have an important role to play when it comes to driving the transition towards a more electrified car fleet. But if there is to be any significantly impact on new registration of electric vehicles, charging infrastructure planning must be based on the demographics of the municipality and its particular geographic constraints.”

Interestingly, the research also revealed that the adoption of electric fleets by municipalities had a significant causal effect on adoption of EVs by private individuals. It’s reasonable to suggest that the visibility of vehicles operated by municipalities is taken by local residents as an encouraging sign that EVs can be effectively operated in the area. And furthermore that if municipalities themselves are committing to EVs, they are also more likely to invest in charging. As the authors note in their study: “the higher the observability of an innovation is, the higher the adoption rate will be."

Of course, other factors greatly impact EV adoption, most notably incentive schemes such as parking benefits, subsidies which improve vehicle affordability and other policy instruments. Nevertheless, the direct relationship between EV adoption and deployment of chargers – alongside additional dynamics at play which are consequential for planning investment into chargers and other supporting grid infrastructure – should be noted by policy makers, municipalities and private groups alike.

Ramping up European charging

A look at the availability of charging points throughout Europe is, on balance, encouraging. While the European Commission has recommended there should be one public charger for every ten EVs on the road, analysis by Transport & Environment reveals that on average across the EU there are currently around five EVs on the road per public charger (updated, July 2019). With increases in both the number of EVs and charging points, this ratio is expected to be around ten to one in 2020. The forecast assumes that EU countries deliver on plans which entail establishing some 220,000 chargers, up from around 170.000 deployed today (Statista).

Transport & Environment also report that the planned European fast charging network will be dense enough to enable later generations of EVs with higher performance batteries and longer ranges to undertake trips through much of Western & Northern Europe by 2020, and throughout the rest of Europe a few years later.

While existing charging infrastructure is far from uniformly distributed – 76% of European public charging infrastructure is concentrated in four countries of the Netherlands, Germany, France and the UK – it should be noted that these countries also represent the top four selling EV markets in the EU.

While the Commission’s target ratio is currently being met, the pace of electrification in Europe is such that continued focus on establishing effective charging infrastructure must be maintained. Moreover, given the costs and scale of forthcoming infrastructure build-out, it’s apparent that it must be built with attention to the kinds of dynamics outlined above.

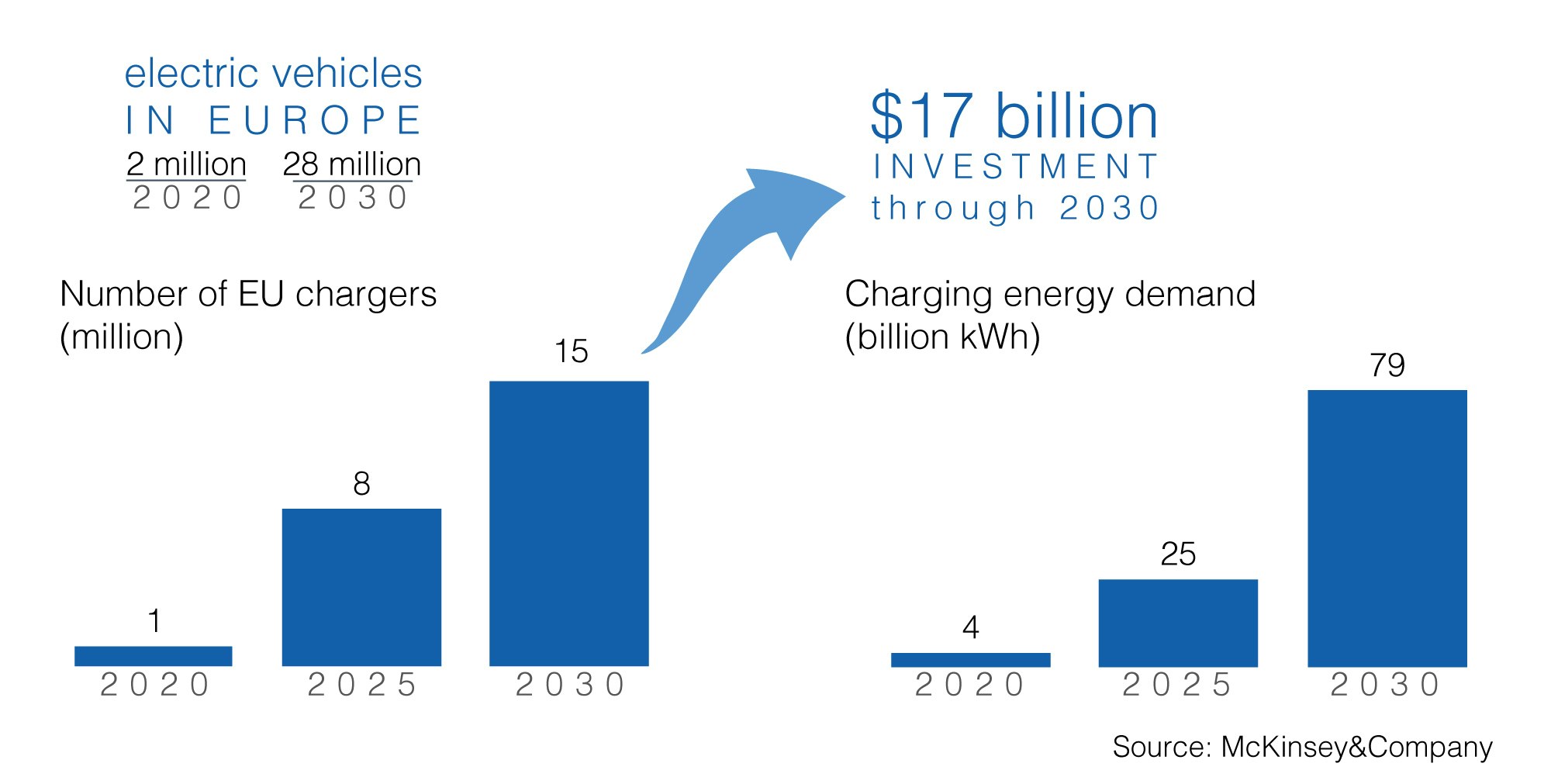

According to estimates by the European Commission, at least two million chargers will be needed in Europe by 2025. However, this figure has been noted as highly conservative. McKinsey, for instance, suggest that 8 million chargers will be deployed by 2025 to meet a base scenario of EVs on the road jumping from 2 million in 2020 to 28 million in 2030 (McKinsey, 2018).

McKinsey also estimates that the EU’s need for chargers will require some $17 billion of investment from 2020 to 2030, to enable some 24 million chargers.

Within this scenario, a charging-energy demand for the European EV vehicle population is modelled at 25 billion kWh. Accounting for that new load is itself a matter for discussion and there are many aspects to consider – including the role of battery energy storage – but it is certainly the case that this circumstance greatly expands the need for smart planning.

“Two things are very clear. Future CO2 reductions depend on greater sales of electric vehicles, and greater sales of electric vehicles depend on a dense network of charging infrastructure. The CO2 legislation must therefore make the link between these two elements.” – Erik Jonnaert, Secretary General of the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association.

Photographs kindly provided by Vattenfall.